By Shirley Qiu

For a while, life in Honduras was fine for one young boy–he lived there with his grandfather while his mother worked in the United States to send money back to them.

As the boy reached his teenage years, however, he began to get recruited by gang members. Though his grandfather protected him for a while, the gang eventually attacked his grandfather. After this incident, his mother and grandfather decided the only option left for the boy was to flee. So he did—to the United States, rejoining his mother and eventually ending up in Des Moines, Washington, with her this past May.

Fortunately for him and other child migrants who have arrived in the Seattle area, several local services help provide for their protection and transition into U.S. society, including shelter and legal and education services.

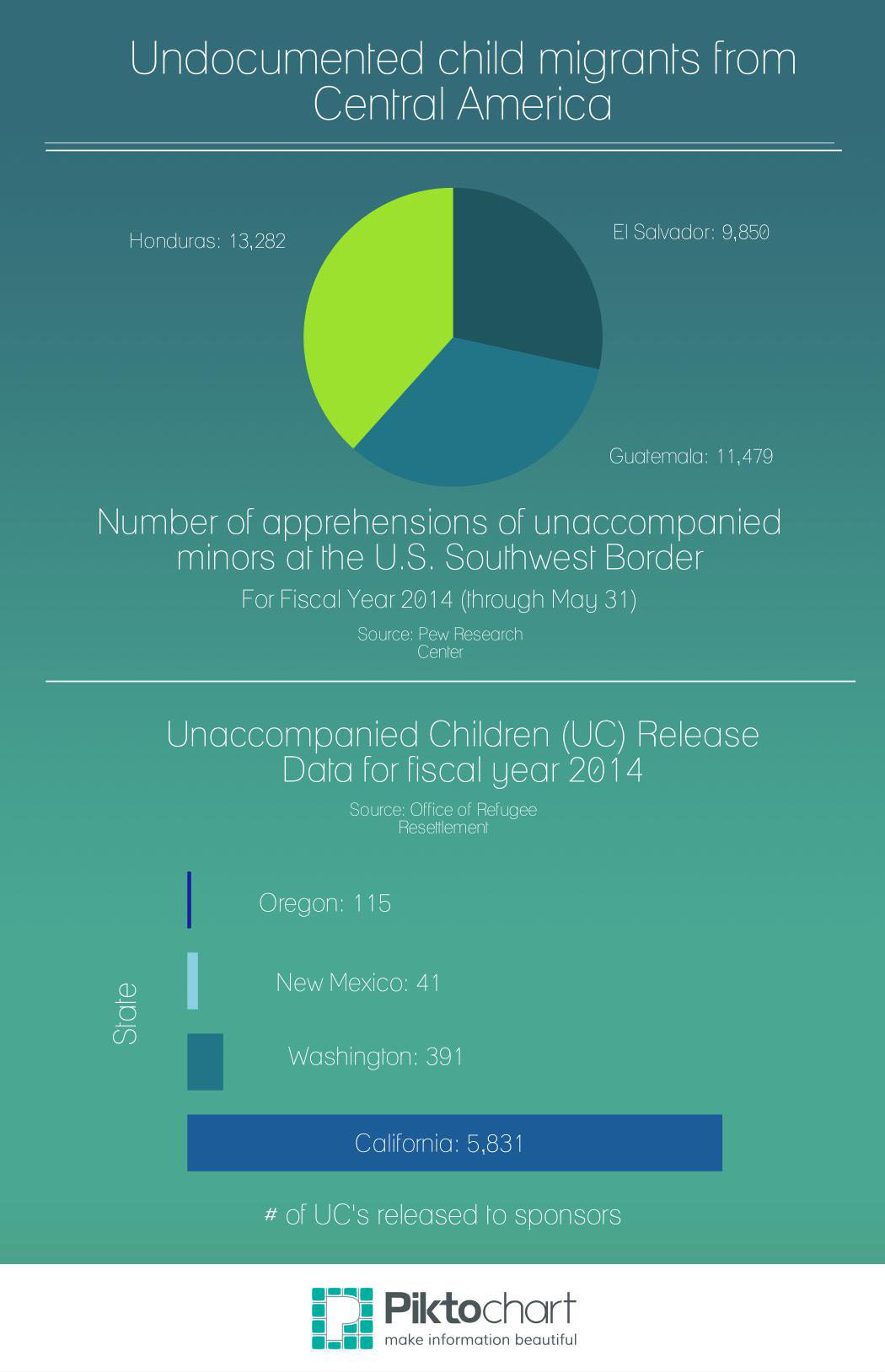

These services are especially important now, considering the significant increase in unaccompanied child migrants crossing the U.S.-Mexico border this past year. From October 2013 to May, just more than 47,000 Latino migrants under the age of 18 were apprehended at the border—nearly double the number from the previous fiscal year, according to the Pew Research Center.

Many are put in detention centers, and many get deported. Others are sent to their relatives in the United States or find shelter at nonprofit organizations. The lucky ones get legal representation. The child migrants who don’t get sent back across the border disperse throughout the United States.

Those children build their new, perhaps temporary, homes here as they await resolution of their immigration status.

A trying journey

In recent years, an increasing number of unaccompanied child migrants have come from Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador.

According to Maru Mora-Villalpando, CEO of immigrant consulting firm Latino Advocacy, much of this is due to violence and other socioeconomic issues in those Central American countries. She shared the story of the Honduran boy above, illustrating the struggles of many children in Central America.

“Kids are coming because…even when they see older children graduating, there is nothing for them—there are no jobs, there’s not even informal commerce happening,” she said. “Violence, of course, is something that they see everyday. Parents are sending money to protect them, but even having money, more in comparison to other families, makes them a target in very poor areas.”

The children who decide to depart for the United States face a long and dangerous journey, which Mora-Villalpando said often takes weeks. To get to the U.S.-Mexico border, most ride la Bestia, “the Beast,” a freight train running from Tapachula in southern Mexico to various points along the U.S. border.

On top of the physical dangers of that, Mora-Villalpando said many face the dangers of the smugglers themselves, who agree to help the children across the border. She said these smugglers, also known as coyotes, sometimes take advantage of the children, selling them to traffickers or to the military in Mexico.

And when they finally arrive, their ideas of the United States, a land of opportunity and wealth, don’t quite match reality.

“I think that any children that watch TV, they think that this is an awesome place,” Mora-Villalpando said. “… [But] They don’t speak the language, they might get bullied at school because they don’t speak the language and because they don’t look like everybody else. Some kids are going through identity crises and they try to fit in.”

Sanctuary in Seattle

For the child migrants here, Seattle is known as a “sanctuary city,” or a city that has policies and services to protect undocumented immigrants.

One of these is a “don’t ask” policy implemented by the Metropolitan King County Council in 2009. Since then, all King County residents can report crime, help out in police investigations and seek out preventative medical care without having to disclose their immigration status.

Other services include legal services provided by organizations such as Northwest Immigrant Rights Project and Catholic Community Services; shelter, coordinated by programs like the Refugee and Immigrant Children’s Program of Lutheran Community Services Northwest; and education services, like the English Language Learners (ELL) and International Programs in the Seattle School District.

Other general education benefits for undocumented children include equal access to education (both before college and during college) and in-state tuition for undocumented college students in Washington state.

“There’s some good efforts in the education arena,” Mora-Villalpando said.

However, she noted, there is much room for improvement, particularly in the area of health care. Because they do not qualify for Obamacare, undocumented children have limited access to health care. They are eligible for Washington Apple Health for Kids and Children’s Health Insurance With Premiums, and under Washington state’s Alien Emergency Medical Program, they have some access to emergency medical care.

Certain organizations in Seattle, however, work to balance out those insufficiencies. Sea Mar Community Health Centers gives health care to anyone, regardless of immigration status, free of charge if the patient’s income level is significantly below the poverty line. Other community health centers in the area that provide low-cost or free care are HealthPoint and Country Doctor Community Health Centers.

The most important thing, Mora-Villalpando said, is for undocumented immigrants to remember that they still have constitutional rights, despite their immigration status. This includes the freedom of expression (at demonstrations, for example) and the right to remain silent during interactions with law enforcement.

“Those are basic things that most people don’t know, and allow for, sometimes, law enforcement to come and take advantage of that,” she said.

Though there is still work that can be done to improve the quality of life for undocumented child migrants and other immigrants in the Seattle area, Mora-Villalpando remains optimistic about the city’s undocumented immigrant services.

“In general, I would say the city of Seattle is a very good city where people, regardless of documentation, can access services,” she said.